While we were planning our strategy leading up to our early retirement in 2012, my husband Rich and I were not too concerned with how to determine whether we had saved enough to last the duration of what we hoped would be a lengthy retirement. My detailed retirement calculator spreadsheet allowed us to model various scenarios that would address that question, based on varying parameters including how much we had saved, at what age we could retire and how much we wanted to spend in retirement.

The bigger, more complicated, and much less discussed issue was how we would structure our savings into an investment portfolio that would easily generate a steady flow of post-retirement income. We were much too young (by multiple decades) to consider an annuity and the traditional strategy of creating a bond ladder (having a series of bonds with staggered maturity dates that freed up cash each year) would not fly given the prolonged and still on-going cycle of dismal bond and GIC rates that pay less than the rate of inflation. Without a company pension or any other source of regular payments such as rental properties, we would need to structure our investment holdings to generate a reliable income stream, which would take some time to set up. More importantly, the payment flow would need to be completed and ready to go before we retired, since we would need to make use of it as soon as we stopped working.

As described in greater detail in our book "Retired at 48 - One Couple's Journey to a Pensionless Retirement", our strategy was to load up on Canadian dividend paying stock, focusing for the most part on blue chip companies with histories of regularly raising their dividends. Our goal was to acquire enough stock to allow us to live off the dividends as our income stream. This defied the common wisdom at the time which advocated to reduce our

equity holdings and acquire a larger percentage of fixed income. We felt less risk in holding stock since we did not care about share price which fluctuates often, but rather the dividend payout which is usually more stable, especially if you select solid companies. Our second decision, that also flouted conventional practices at the time, was to collapse our RRSPs into RRIFs immediately after retirement. This enabled us to spread the source of our retirement income across both registered and non-registered accounts, making all of them last longer. It also helped to reduce the size of our registered accounts slowly over a longer period of time, optimizing our overall tax burden. These days this strategy is regularly recommended by financial advisors and analysts, but at the time when we decided to do it back in 2012, we were definitely going against the tide. Our two strategies have served us well. Over the past 7.5 years since our

retirement, our steady stream of dividend income acts like a bi-weekly pay cheque and has continued to grow at a rate that so far has outpaced the rate of inflation.

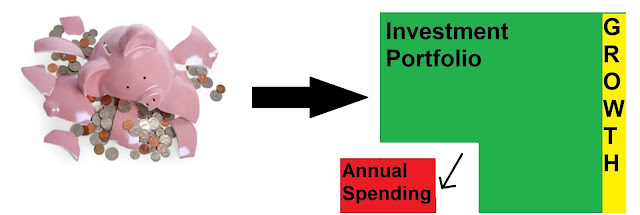

It took many years for us to accumulate a stock portfolio large enough to live off our dividends. I started to consider what our strategy would be like if instead we needed to sell capital annually from our investments in order to fund our retirement. In reading investment columns like the ones in the Globe and Mail, I noticed that the advice given usually went as far as to discuss the order which various money sources (RRIFs, TFSAs, non-registered, cash balances) should be tapped, but did not go into detail on how this actually would work. Giving it some thought, this is what I think I would do:

I started with the assumption that we had still amassed a portfolio consisting of mainly Canadian dividend-paying stocks during our retirement savings period, but that it did not generate enough dividends to support our income needs. Until the returns in the fixed income market improve significantly, we

would still want to hold stock, but

we would need to take steps to reduce risk since now we do care about fluctuating

stock value. Luckily we happen to have a high risk tolerance that allows us to stay calm during large

swings in the market. This is not so for everyone.

With our current strategy of living off our dividends, our investment portfolio is diversified across all of our accounts but not within any particular account. This is because we are not regularly selling stock. We initially withdrew the annual minimum from our RRIF accounts, requesting an equal cash payments monthly. Recently we switched to requesting withdrawal of stock-in-kind from our RRIFs to our shared non-registered account, in order for future dividend income from this stock to be taxed at a more favourable rate.

If instead we were required to sell part of our investment portfolio each year, this would

change how we structured our holdings and withdrawal strategy. In each of our

RRIF accounts, we would re-balance our holdings to increase the number of different stocks that we owned there, covering different sectors in order to have good diversification.

This would

allow us the flexibility each year to pick which stock to sell or not,

depending on whether one sector is performing better than another, or if a

specific company is having an unusually bad year. We would also

consider buying US or Foreign market ETFs in order to maximize

diversification, but I prefer holding Canadian stock as opposed to a

Canadian ETF since we have more control of what we are selling. In choosing which stock to sell, we might pick one that had increased

in value, locking in the capital gain while allowing lesser performing

stock time to recover. Alternately we might cut our losses on a dud

stock that doesn't seem like it would recover any time soon, if ever.

If we had to decide between two equally qualifying stocks, we would keep

the one that had more dividend growth history and potential.

Unless we were in midst of a prolonged market downturn, each year we would sell some stock in each of our RRIF accounts (ensuring to sell enough to cover any withholding tax owed) and make a single withdrawal. The cash from this sale would be supplemented with any dividend income paid from our non-registered accounts, and eventually CPP and OAS payments, to make up our annual income requirements for that year. We would open a special high interest savings account to receive this money so that it continues to earn interest as we spend it throughout the year. We would set up automatic monthly transfers to our bill-paying chequing account to cover the upcoming month's estimated expenses. We use the CDIC-protected EQ Bank which has been paying

2.3 percent annually on its savings accounts for several years now.

This rate currently beats most fixed income offerings as well as the

estimated rate of inflation, and our money is totally liquid as opposed

to being tied up for the specified terms of bonds and GICs. We also get 5 free Interac transactions per month, but that's another story.

In order to have maximum control over when we sell our stock, we would

set standing default instructions with our discount broker to withdraw

the minimum from our RRIFs at the END of the year. These

instructions can be overridden at any time during the year, and allows

an entire year to choose the right time to sell our stock. This means though that our "annual income" savings account needs to have enough cash to support waiting until the end of the year to sell, or else we need to borrow from our long-term emergency funds. Since we would

not be selling all of our shares in any year, we would set up Dividend

Reinvestment Plans (DRIPS) and Dividend Purchase Plans (DPP) for all of the

stock in our RRIF accounts, so that the ones we don't sell for the year

will continue to grow on a compound basis.

We would hold much larger cash balances than we currently do within our long-term emergency fund accounts (currently also at EQ Bank), with enough money to cover at least 2+ years worth of retirement income. This money could be used to temporarily tide us over if we needed to wait out downturns in the stock market and would act as our secure "fixed income" buffer until bond and GIC rates recover enough to be worth purchasing again. At that point, we could once more consider creating a bond or GIC ladder.

At the end of each year, I would analyze the rate of depletion of our investment portfolio against our initial retirement plan to make sure that we were on track and adjust our spending accordingly the following year if we were not. I do this now even with our dividend strategy but it would be so much more important than ever to do if we needed to sell capital annually.

Just thinking through this academic and theoretical situation has been a lot of work and quite stressful since it is clear that the risk involved is much higher than our strategy of living off our dividends while retaining our capital for as long as possible. I'm not sure how viable this plan would be since we are not implementing it, but at least it is a comprehensive plan whereas I fear many people retire with no plan and I wonder what they do then? I am not in any way recommending my hypothetical plan for others, but I guess the message is that you should think about how to generate retirement income ahead of time and implement a plan that suits your needs and risk tolerance (or have your financial advisor do it for you, but hopefully it is more detailed than "You should take $X out of your RRIF each year").